Presented by Chicago Film Society

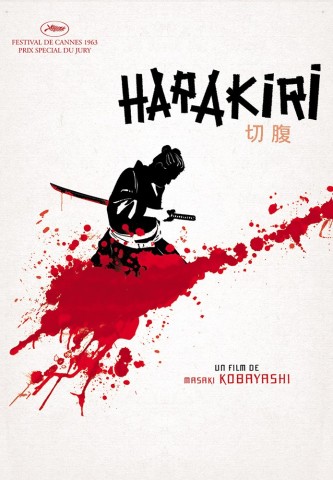

One of the great movies about honor (and unemployment), Masaki Kobayashi’s samurai drama Harakiri tells “the hardscrabble tale of a rōnin,” who arrives at the gates of the Iyi clan to share his story and commit seppuku in their courtyard. Of course this is no simple request; the rōnin might actually have a bone to pick with the clan. The story takes place in 1630 (with a generous dose of flashbacks) during feudal Japan’s Edo period, when the Tokugawa family ruled the country. Kobayashi, a pacifist who had been drafted into the war effort in the early 1940s, had a strong aversion to feudalism, hierarchy, and submission to authoritarian power. The historical setting allowed him to explore his interest in postwar Japanese social issues — chiefly corruption, hypocrisy, and denialism of war atrocities — in the guise of a jida-geki, or period film. He first (and more explicitly) explored these topics in undersung yet equally fascinating films, including the sleek, cynical noir The Inheritance and the epic war drama trilogy The Human Condition. Harakiri was released to great international acclaim, taking the Special Jury Prize at Cannes and establishing Kobayashi as a modern master. The visually splendid Harakiri was photographed by cinematographer Yoshio Miyajima (Kobayashi’s frequent collaborator); every shot is rigorously considered, starkly framing both simple human figures and acts of devastating cruelty. As a work of political art, it is as satisfying as it is electrifying — Kobayashi holds a mirror up to his own century’s societal corruption by reckoning with the prolonged influence of the Samurai code, questioning its validity through magisterial storytelling.

Recommended Films